Pasar Malam

It is easy to get lost here. No one would notice if I was swept away in this mosaic river of locals who brave this market rush hour every day. My mom is surveying an assortment of crispy fish balls on sticks. My brother is next to her, sipping a grass jelly drink with boba. My dad is out of sight, lost in this ocean of people—he must be where the row of tents end, buying a bag of sweet rambutans.

From dusky sundown to moonlit-night, this street is a breathing torrent of bustling activity. It is all too easy to get carried away by the fluid motion of customers sauntering from vendor to vendor. I’m swerving through the flood of skin and hijabs when I notice up ahead the crowd parting as a rock divides the river. I move with the stream of people until I reach the rock that I can’t see. That’s when I nearly step on him.

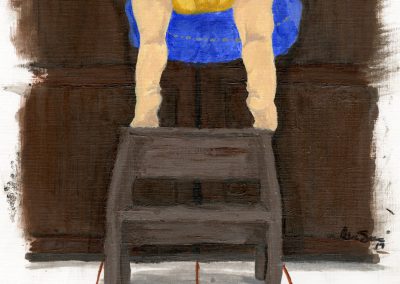

He is sprawled on the floor, belly flat against the tar of the road. His skin is brown and sunbaked and wrinkled, like tree trunks. His arms are stretched in front of him, hands like twisting branches clinging to a tin can half-filled with dollar bills and spare change. Where his legs are supposed to be, only the tail ends of his dirt-covered shirt conceal two stumps.

People step around the legless, homeless beggar. Their eyes dart elsewhere—to the stand of socks, to the family buying Chinese yo-yos, to the girls selling cheap jewelry. They swerve out of his way as if he is Moses parting the Red Sea, only he has no staff to give him dignity.

He is banging his head against the ground. Words have escaped this man. “Please,” he has learned, is not sufficient. The world has reduced him to the most primal form of begging because pity is not enough to halt people in their tracks and give him what they can. He has learned guilt is the best incentive of all.

I take a step away from him, and another. My mind can’t shake the image of him, but I am, like everyone, a creature subject to the laws of inertia. It is hard to stop our movement as we propel through life, or crowds, and before I know it, I am tents away from him. I spot my dad, and the same inertia propels my hand to tug on his sleeve. He takes out his wallet and gives me what I asked for.

Turning around is much harder. Now I am vulnerable as I crouch in front of him and place the crumpled bill in the can. His eyes meet mine, and for a moment I think I may have stopped his vicious cycle of banging, but his head hits the ground again. And again. And tomorrow when the pasar malam returns with its tarps and smoke and people pressed in close proximity, he will still be here, gravel embedded in the creases of his skin. I wish I could give him more than money and a prayer. I picture myself catching his forehead before it hits the ground, stopping his inertia, holding him close until he stops shaking. I want to give him everything I have.

Instead, I stand and push my way to my parents, who are buying charred satay. I cling to them, wrapping my arms around them like a relentless tree branch as the crowd sweeps by.

Writer: Cassandra Hsiao is in the Creative Writing conservatory at the Orange County School of the Arts and an editor of her school’s award-winning art and literary magazine, Inkblot. Her work has been nationally recognized by the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards and the National Student Poets Program. She also conducts print and on-camera interviews as a Star Reporter and Movie Editor for multiple online outlets.

Artist: Eesha Azam Khalil moved to California from Pakistan. She studied Graphic Designing from Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture in Karachi, Pakistan. Passionate about Animation, her move to California was a perfect fit. In her free time, Eesha loves to go hiking and taking pictures.

More Articles